Well done!

-

-

Thank you!

-

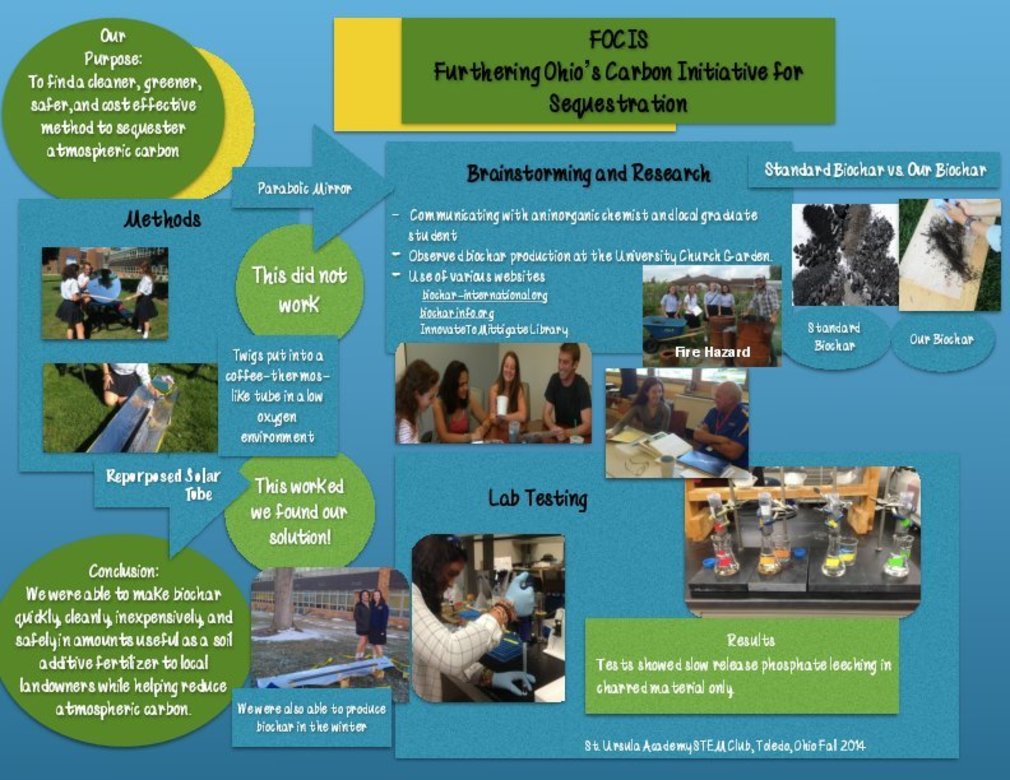

Your project reflects alternative thinking and shows how one idea: green carbon sequestration, leads to another: soil enhancement: while also rejecting a common belief: biochar can be used as a soil run off filter.

-

Congratulations SUA Scholars! Decreasing atmospheric Carbon one solar tube of Biochar at a time! Thanks for helping make our atmosphere more healthy and sustainable.

-

Hi Team FOCIS — great job! Just one question — why did you choose phosphate absorption as the way to test your biochar?

-

Thanks for your question! The answer is a little bit roundabout. We originally started looking at biochar as a way to filter out phosphorus from fertilizer runoff from fields into waterways. Phosphorus ending up in waterways leads to algae blooms which lead to all sorts of other issues. However, we learned that instead of taking phosphorus out of water, water run through the biochar actually ended up with more phosphorus in it than before. This definitely limited the potential of biochar as a filter for runoff, but it opened a whole new approach to the project, using biochar not only for carbon sequestration, but also as a natural fertilizer, and that was the approach we pursued. Hopefully that makes sense! If you have any further questions, we’d be happy to answer them.

-

Further posting is closed as the event has ended.

Susan Leschine

Professor

Great project! Terrific title & acronym! I have a few questions:

What is the size of your repurposed solar tubes? What was their original use?

How much biochar can you produce/tube? Can you envision ways to scale up your biochar process?

Beatrice Thaman

Thank you for your comment, Ms. Leschine.The solar tubes are 6’ x 2 1/2”. The original use of these tubes was heating water for an alternative form of indoor house heating. They were then modified as solar tubes that heated air.

The maximum volume of biochar we can produce in one tube is 200 square inches, although this depends on the particle size of the biochar. To scale up our biochar process we envisioned an automated system of filling the tubes with a machine, and then sending the tubes out into the sun on a conveyor belt during the day. After this process we would empty the tubes and then package the biochar. Our team has also begun communicating with gardens throughout our community to start implementing our biochar and also to get them interested in producing their own biochar.

Gillian Puttick

Senior Scientist

Great project – I specially appreciated your repurposing of existing materials, which also mitigates greenhouse gases, and how you clearly described your investigation process clearly in the video. Can you speculate about the approximate quantity of carbon sequestered per tube of biochar?

Beatrice Thaman

Ms. Puttick, that’s definitely an important question. While we did have the exciting opportunity to do lab testing at the University of Toledo, we chose not to test the carbon sequestering properties of the biochar. There has already been so much research done on carbon sequestration through biochar, especially by organizations like Biochar International, that we thought we might be more productive studying another interesting aspect of our biochar, like its phosphorus output. Combining our research that shows how useful the phosphorus is as a fertilizer with Biochar International’s research that shows that 20% of the carbon in the organic materials used to make biochar does not return to the environment, we were confident that the biochar would be good for the environment in more way than one.

Brian Drayton

Co-Director

FOCIS Team! Nice project, and nice presentation.

My question is related to Susan’s — What’s special about the solar tubes you used? I mean, how hard would it be for someone to use a different kind of container?

Beatrice Thaman

That’s a great question, Mr. Drayton, and definitely one we found ourselves facing at the beginning of our project. The traditional way to make biochar is through a double barrel system, with the barrel sizes ranging from one gallon to fifty, depending on the amount of biochar you would want to make. We got a demonstration of this method early on in our project, but we wanted to find a way to make the biochar without the danger of an open flame, and also to recycle materials from our community. The solar tubes satisfied both of these qualifications. By using the power of the sun, we don’t have to have an open flame, and the solar tubes are made by Owens-Illinois, a company based in Toledo, where we live. It’s definitely possible to make biochar through a variety of different methods, but we found this one especially efficient and environmentally friendly. Hopefully that clears it up a bit!

Sara Lacy

Senior Scientist

Interesting and clear presentation. I’m eager to learn more. Are there many used solar tubes available for reuse? If not, how might you make or procure others? How is the “Low oxygen environment” created? Do you know what the temperature was in the tubes?

Beatrice Thaman

Ms. Lacy, we know that the scalability of a project is very important, and so that was one of our main focuses for the project. In Toledo, where we are located, there are approximately one hundred solar tubes sitting in a warehouse, unused. That’s just in Toledo. Nationwide there are thousands, all of them just taking up warehouse space. Because this technology is not being used for heating homes anymore, it would be relatively simple in terms of having the technology to first scale up our project in Toledo by using the hundred tubes, and eventually on a national scale by mobilizing people where these tubes are left unused to start their own biochar projects. These thousands of tubes will last for a long time, but if needed, Owens-Illinois could manufacture more if the demand was high enough.

As for the environment within the tubes, we achieved a low oxygen environment by limiting the access of air into the tube. One end of the tube was sealed off, and we loosely covered the other end with tinfoil so that a moderate level of oxygen was available for the proper manufacturing of biochar, but so the biochar would not become overly exposed to oxygen. We measured the temperature inside the tube at regular intervals, and discovered that at the highest temperature, the interior of the tube reached 600 degrees Fahrenheit, which is an appropriate temperature for creating biochar.

Joni Falk

Co-Director, Center for School Reform

I learned a lot, thanks. How did you get involved in this topic to begin with? And did this spark an interest in your team members in continuing this work or related projects? Would love to hear.

Beatrice Thaman

We definitely learned a lot in our research, too, Ms. Falk. When we first heard about the Innovate to Mitigate challenge in June of last year, we started looking over the topics to choose one that interests and excites all of us. One of our team members works in a community garden, where they use biochar as a natural fertilizer. She was really interested in the idea of biochar as a form of carbon sequestration, not just as a fertilizer, and so we pursued our project in biochar. Going forward, we’re continuing to work with Toledo-area farmers and growers to use our biochar when they begin planting in the spring. In addition, one of the members of our team became so interested in the project that she is pursuing a summer internship in the same lab where we did our testing. We can’t wait to see what else we can do with this project!